- Home

- Allen Hoffman

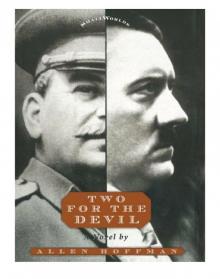

Two for the Devil

Two for the Devil Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

THE LETTER

I - ROYAL GARMENTS

PATRIARCHS AND PROGENY

CHAPTER ONE

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

CHAPTER SEVEN

CHAPTER EIGHT

CHAPTER NINE

CHAPTER TEN

CHAPTER ELEVEN

CHAPTER TWELVE

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

AIR WAVES

II - THE STRENGTH OF STONES

DEFINITIONS AND FINDINGS

THE GHETTO

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

CHAPTER NINETEEN

CHAPTER TWENTY

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

CHAPTER TWENTY TWO

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

CHAPTER TWENTY - SIX

CHAPTER TWENTY - SEVEN

CHAPTER TWENTY - EIGHT

CHAPTER TWENTY - NINE

CHAPTER THIRTY

CHAPTER THIRTY - ONE

CHAPTER THIRTY - TWO

CHAPTER THIRTY - THREE

CHAPTER THIRTY - FOUR

SOUND WAVES

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Copyright Page

We hope you enjoy this book from Abbeville Press. To write to the author or see our other titles, click here. (This link will open your device’s web browser.)

For Bob Abrams, Publisher and Friend

Is my strength the strength of stones? or is my flesh of brass?

—Job 6:12

THE LETTER

FOR YEARS THE REBBETZIN, SHAYNA BASYA, DUTIFULLY placed Postum and Aunt Jemima pancakes before the rebbe in the morning, and Yaakov Moshe Finebaum dutifully consumed them. After breakfast, the rebbetzin placed pen and paper on the rebbe’s desk; but even though he spent long hours alone in his study, the rebbe never touched them. When she encouraged him to write to their daughter, Rachel Leah, in Russia, he would nod agreeably and explain, “When the time is right.”

There were moments when the rebbetzin thought the time might be right. In 1923, after Warren Harding died and Silent Cal Coolidge entered the White House, the rebbetzin noticed that the pen and paper had been used. But one morning, the rebbe pointed with disgust at a campaign picture in the St. Louis newspaper of Calvin Coolidge posing in an Indian warbonnet. In the background, his chauffeur and limousine waited to whisk him away. “An impostor, a fake,” the rebbe declared angrily and stalked into his study. The next morning, Shayna Basya again found the writing materials untouched.

They remained that way until 1927, when Charles A. Lindbergh made his historic solo flight across the Atlantic. “The Spirit of St. Louis,” the rebbe mused conspiratorily, savoring the name of the heroic aviator’s craft. “Our son-in-law, Hershel Shwartzman, could fly it back here for him,” he suggested, picking up the pen. The rebbetzin didn’t respond. As far as she knew, Grisha, their son-in-law, couldn’t pilot a plane. Even if he could, Lindbergh had flown solo; there wasn’t any room in the “Spirit of St. Louis” for Rachel Leah. It made no difference, however, for the rebbe suddenly ceased writing when the newspaper worshipfully referred to Lindbergh as the “Lone Eagle.” “A trayf bird, grasping impurity,” he pronounced, sadly shaking his head. Despairing of his ever writing to their daughter, Shayna Basya stopped providing him with pen and paper.

In 1936, Reb Zelig, the rebbe’s sexton, fell ill and died. On a steamy summer day, they buried him, and upon returning from the cemetery, the rebbetzin opened the icebox for a cool drink.

“Would you like something?”

“Yes,” he answered, sweat covering his smooth forehead in an unbroken watery film, as if he had just surfaced from a deep pool.

“What?” she asked.

“A pen and paper,” he demanded.

“Whatever for?” she asked.

“If I don’t write now, the letter won’t arrive before Rosh Hashanah,” he explained matter-of-factly.

The rebbetzin followed him into the study and presented him with pen and paper. “Thank you,” he said, and began writing at once.

Fifteen minutes later, she was sipping a cool glass of water at the kitchen table when the rebbe returned with the letter.

“That was quick,” she commented.

“Sixteen years, and you call it ‘quick,’ ” the rebbe said, slightly bemused.

“Would you like a drink?” she asked.

“A beer, please.”

She looked up in surprise. The rebbe had never shown any taste for the beverage.

“Yes, Prohibition is over,” he stated.

She placed the cool bottle on the table; at once a fine mist shrouded its dark surface. She pushed the letter away so it wouldn’t get wet.

“Thank you,” he said, but she didn’t answer.

She was staring down at the envelope addressed to her son-in-law. Prohibition had ended in St. Louis. The rebbetzin wondered how her daughter and son-in-law were welcoming Rosh Hashanah, the New Year, in Moscow in 1936.

I

ROYAL GARMENTS

If a king’s porphyra, royal purple garment, appears as merchandise in the market square, woe unto the seller and woe unto the buyer. Thus Israel is the royal purple garment in whom the Holy One is glorified for it is written “Israel in whom I (God) am glorified . . .” (Isaiah 49:3) and, consequently, if Israel becomes common merchandise, it is woe unto the seller and woe unto the buyer.

—Midrash Esther Rabba

MOSCOW

1936

ROSH HASHANAH

(THE NEW YEAR)

It is taught in the name of Rabbi Eliezer that the Sixth Day of Creation fell on Rosh Hashanah, the New Year. On that day Adam was created from the dust, was placed in the Garden, was commanded not to eat of the Tree, sinned, in the eleventh hour he was judged, and in the twelfth hour he was pardoned. The Holy One Blessed Be He said to Adam: Just as you stood before Me in judgment on this very day, Rosh Hashanah, and you were pardoned, thus in the future your sons will stand before Me in judgment on Rosh Hashanah and they, too, will be pardoned.

—Vayikra Rabba

Rabbi Yossi Bar Kazarta taught: The Holy One Blessed Be He said to them, since you entered in judgment before Me on Rosh Hashanah and went forth in peace, I consider you as if you are a new creation.

—Jerusalem Talmud, Tractate Rosh Hashanah

PATRIARCHS AND PROGENY

NEITHER YAAKOV MOSHE FINE BAUM, THE KRIMSKER Rebbe, nor Karl Marx, the social philosopher, ever visited Moscow. Both, however, engendered offspring who resided in the traditional capital of Russia.

Karl Marx, the father of scientific socialism, based his materialistic determinism on the critical dialectic. The critical dialectic taught that the interaction of antagonistic, dynamic forces leads to change, and these new developments in turn lead to further dialectic progress. By means of the dialectic, Marx had declared that the workers had nothing to lose but their chains.

Inheriting the mantle of leadership from Marx, in 1903 Lenin created bolshevism when he falsely declared the men of his party faction to be of the majority, the Bolsheviks, and the opposing faction to be of the minority, the Mensheviks. In 1917 Lenin led the Bolsheviks in the Great October Revolution, and Russia became the world’s first Communist-Marxist state. Tirelessly Lenin advanced the dialectic: since the workers had already lost their chains, he murdered the tsar.

Later, when Lenin lay ill, he warned the Communist par

ty against Comrade Stalin, the general secretary. In spite of this, Stalin inherited power, and he, too, quickly employed the critical dialectic by declaring that Lenin had bequeathed the Marxist-Leninist-Bolshevik legacy to him.

As Lenin’s Bolshevik heir, Stalin continued the development of the critical dialectic; since the workers no longer had chains and the tsar had been murdered, Stalin demonstrated the virtues of a classless society: absolutely everyone except Stalin could be the enemy. Even the party itself was subject to bloody purges. As for the workers, Stalin imprisoned, tortured, and murdered them, and he did this in numbers that the tsar had never dreamed of, because with the critical dialectic, progress knew no limits!

By contrast, the Krimsker Rebbe’s only daughter, Rachel Leah Finebaum, knew very specific limits. In Moscow she lived in stagnant isolation in an armoire. Her husband, Hershel Shwartzman, a senior colonel in the Soviet secret police, the NKVD, did not have to be an expert practitioner of the critical dialectic to understand that the wife of his youth was quite literally the skeleton in his Marxist-Leninist-Bolshevik-Stalinist closet. And he knew about creating skeletons; Colonel Shwartzman worked to protect the world’s most progressive revolution in the world’s most Stalinist secret police prison, the Lubyanka.

The Lubyanka was both limited and limitless because of its sacred mission: to insure Stalinism. Like everything else in Stalin’s Soviet Union, the Lubyanka had a past as well as a present. Under Stalin, either or both could prove to be liabilities. The Lubyanka’s past certainly was an embarrassment, for it had been the home of a bourgeois insurance company.

CHAPTER ONE

WHO COULD DOUBT THE TRUTH OF SUCH A BUILDING? Certainly not Colonel Hershel Shwartzman! Inspiring confidence, symbolizing stability, the great massive structure had been the Rossiya—Russia Insurance Company. The Rossiya had successfully insured bourgeois lives against death, a mere physiological necessity, but eventually it failed; nothing could insure bourgeois life against a historical necessity, proletarian revolution. The tsarist Rossiya fell in a blaze of red glory to the Great October Revolution, but the imposing, massive edifice remained. Purged of its parasitic despoilers, it began a new life that only a revolution can bestow—and vigilantly served all the people in the noblest of pursuits, safeguarding the Communist revolution.

To compare the new Soviet workers’ communal society with the preceding rotten exploitative capitalist one was an outrage. Where once there had been darkness, there was now light. How could one compare darkness and light? Aside from the moral travesty, it really was quite impossible. Still, if one were foolishly to risk such an absurd undertaking, one might suggest that the liberated building, now populated with the “new” Soviet man, continued to serve a remarkably similar function: insurance.

The Lubyanka actively insured the success of the world’s only Communist revolution. It was busier than before and, understandably, more densely populated, for the Lubyanka was the secret police prison, the very home of the NKVD, the Soviet secret police. Of course it was busier: the tsarist Rossiya had to worry only about death, fire, flood, famine, and other natural events, but along with these insignificant occurrences, Stalin’s protectors contended with Mensheviks, Trotskyites, kulaks, “former people” (tsarists), revisionists, anarchists, Social Revolutionaries, counterrevolutionaries, wreckers, double-dealers, saboteurs, spies of every ilk, engineers, all clerics, Ryutinists, fascists, right oppositionists, Bukharinists, left oppositionists, White Guards, capitalists, and most old Bolsheviks, to name a few.

All of these “unnatural” but cunning enemies were enmeshed in conspiracies, constantly hatching plots. And they were ubiquitous; they had even been unmasked posing as loyal party members. It was enough to make one’s head spin, and NKVD colonel Hershel Shwartzman’s had spun for the last several years. But now he was overwhelmed by it all. What had set his head turning most, however, weren’t the frantic investigatory white-hot beams of NKVD light so much as the elusive shadow that played among them. That shadow was the staple of all insurance organizations: fear.

Fear had always made the denizens of the Lubyanka do strange things. Since the Lubyanka represented a progressive revolution, fear, too, had progressed; it caused the secret police officers themselves to do strange, unexpected things within the sheltering walls where Grisha Shwartzman now sat, facing a prisoner. Bourgeois insurance divided the risk, but Communist security multiplied the fear.

Never mind the fear, Grisha thought; but who could put that from his mind? It was always lurking like a shadow in the darkness. The light would shine, but there it would be, naked and ugly. Beyond the fear, the NKVD officer marveled; it was positively shameful! Grisha should have returned the prisoner to his cell almost two hours earlier. What was worse, he, an NKVD colonel, was permitting the prisoner to sleep. That was a scandal. Almost a sacrilege. When Colonel Hershel Shwartzman had taught interrogation, if a trained lieutenant so much as permitted a prisoner to close an eye, Grisha had mercilessly roasted the fledgling officer for lacking revolutionary vigilance. The officer never lacked it again; not if he wanted a real investigatory career in the NKVD. If not, let him guard convoys, administer camps, supervise institutions. There was more than enough to do, but if the cadet really wanted to protect the revolution by rooting out the evil that threatened to sap its lifeblood, he would listen.

Who could appreciate that lifeblood better than an old Chekist who had struggled to create the very revolution itself? The very first political institution created following the Great October Revolution was the Cheka—whose initials stood for Extraordinary All-Russian Commission of Struggle against Counterrevolution, Speculation, and Sabotage. Not until a month later did the party establish the Glorious Red Army under Trotsky, that traitor. There was a man who split the party and damaged the state! The Chekists, however, were loyalty itself. The party’s founder had enrolled Grisha in the fledgling organization. Oh, Grisha had taught them a thing or two. And now? Chekists themselves were not only suspect but even more suspect than anyone else. Why? Why those who had served so faithfully, the sword and shield of the revolution?

In the past few years, when his head had spun, Grisha had hoped that things would settle down and his head would cease to spin. Everything would fall into place and begin to make sense. He wanted to stifle the swirling chaos he was afflicted with—as a dizzy child reels, stumbling off a carousel—until little by little, the world would stop gyrating and once again only the carousel would revolve, balanced and bright, a large child’s toy. Now Grisha realized there might be no climbing off the ever quickening machine. Disoriented, he would inevitably lose his grip and be flung off, to crash against stable objects such as the prison bars of the Lubyanka itself. Or worse, flung into the basement, where the dreaded pistol shots had no echoes.

Colonel Shwartzman had feared for the revolution; now he feared for his life. Others who had ridden the carousel more skillfully—moving to the very center, where the motion was negligible—had been thrown to their deaths. Henrik Yagoda, the chief of the NKVD, had disappeared. Grisha had not been allied with Yagoda; those who had, immediately followed the ex-chief into the basement. Until Yagoda’s precipitous fall, Grisha had always assumed that he himself had an insurance policy against casualty. Grisha had served Stalin faithfully from the beginning. Not personally, but he had never made a secret of where his loyalties lay. After beloved Lenin’s death, Grisha had understood that Stalin was the only man for the job. But look what had happened to Stalin’s man, Yagoda. No, with Stalin there were no insurance policies, only sacrosanct areas where the NKVD would not arrest one of their own. The organs could never admit a mistake; therefore, no NKVD officer could ever be arrested while interrogating a prisoner. As long as the prisoner in front of him remained, Grisha was safe. Two hours ago he should have returned him to his cell. How much longer could he keep him here?

Grisha stared across his desk at his insurance. An experienced prisoner, the man sat erect. Anyone entering the office from behind

would never suspect him of sleeping. His eyelids were inflamed and puffy from days without rest. Grisha guessed that his companion was about his own age, slightly over fifty, but the man had been in prison camps before he was returned to the Lubyanka, and he looked considerably older. For all the discomfort of the prisoner’s predicament, his unguarded expression revealed something smug, as if the NKVD were not worth losing sleep over. Jealous that the man could rest so innocently, Grisha felt a rush of the old Chekist indignation at the prisoner’s contempt for Soviet justice. A Chekist colonel had a sense of pride! Suddenly, Grisha went around the desk and kicked the prisoner in the shin. The man’s eyes popped open, and he instinctively began to rub his leg.

“Mock Soviet justice!” Grisha cried indignantly. He wasn’t acting. He felt the burning hatred welling up within him as if he had swallowed hot lead.

“We know everything. We know everything about you,” Grisha railed. “You!” He wanted to spit out the prisoner’s name, as if even pronouncing it left a bad taste in a decent man’s mouth, but for the life of him he couldn’t remember. He wanted to check the name on the folder lying on his desk, but he thought better of it. The organs were infallible and omniscient.

“You Trotskyite wrecker!” He uttered these words with the abhorrent loathing he felt for all those who had followed that arrogant theoretician. Stalin had gotten that right!

The prisoner looked slightly bewildered. Grisha had caught him with his guard down. Now was the time to press the advantage.

“Do you still deny it?” Grisha snarled.

Perplexed, the prisoner shifted his weight.

“Answer me,” Grisha demanded.

Small Worlds

Small Worlds Kagan's Superfecta: And Other Stories

Kagan's Superfecta: And Other Stories Big League Dreams (Small Worlds)

Big League Dreams (Small Worlds) Two for the Devil

Two for the Devil